15 July 1941. Postscript: Britain’s prime national radio slot, straight after the nine o’clock evening news, broadcasting to one in every four adults across the country.

I have come to tell you tonight the story of a rich man trying to make his last and greatest sale – that of his own country.

It is a sombre story of self-respect, of honour and of decency being pawned to the Nazis for the price of a soft bed in a luxury hotel.

It is a tale of laughter growing old and of the Judas whine of treachery taking its place.

Uniquely in the BBC’s long history, all editorial controls had been overridden on government orders for the seven-minute demolition of the reputation of a national treasure.

There seem to be running themes in the lists of famous alumni that public schools hold so dear; Eton for example does aristocratic prime ministers. When I first found myself at South London’s robustly middle-class Dulwich College, I learned that the local specialities were arctic explorers, long-retired sportsmen, and mass market authors.

There was only the one explorer of note, but he was a daily, if rather dusty, presence in our lives. An open boat sat in the passage between two of the school’s grand Victorian blocks; this, we were told, was ‘Shackleton’s boat’. Nobody really bothered to explain to us the story of its desperate five-man, fifteen-day voyage across the South Atlantic in storm force winds. A once sacred relic of Edwardian derring-do, the small vessel remained untouchable – but with Dulwich determined to adapt itself to the zeitgeist of the Seventies, there seemed no need to dwell on it.

A few years later, another piece of alumni clutter arrived: the Long Island study of a man with one of the stronger claims to be the twentieth century’s greatest comic writer - dismantled and shipped across the Atlantic to be rebuilt, typewriter, pipe-rack and all, in the middle of the school library.

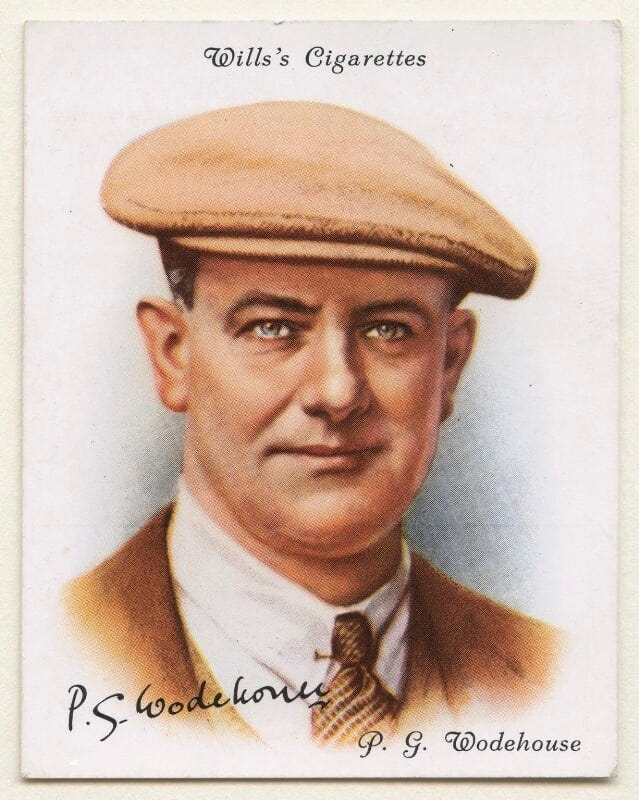

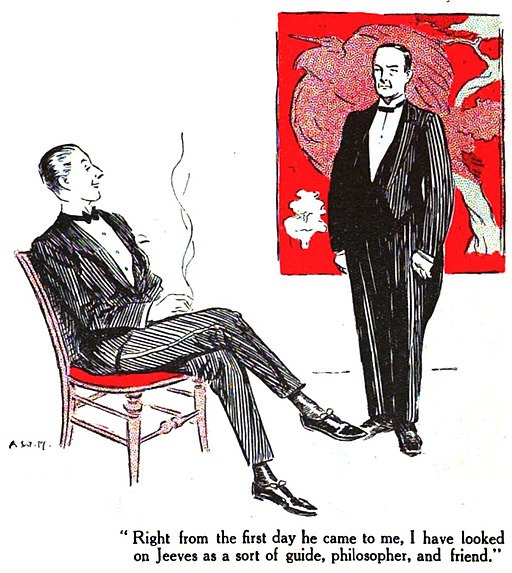

P.G. Wodehouse was one of a quartet of best-selling old boys. Most of us had read C.S Forester’s Hornblower books, the beginning of a whole genre of Napoleonic sea adventures. Dennis Wheatley’s page turners were mediocre but hugely popular, particularly his occult thrillers where clean-cut British heroes battled rich and powerful satanists with thick European accents. Raymond Chandler, we knew mostly from television reruns of black-and-white Humphrey Bogart movies made from his hard-boiled private eye stories. Wodehouse himself of course had brought us the bottled sunshine of Blanding’s Castle, Bertie Wooster and the wise and ever resourceful Jeeves.

Wheatley was the black sheep of the group, expelled from the school, he claimed, for founding a secret society. Very much on brand. But with Wodehouse too, more puzzlingly, there was some sort of a shadow, never fully explained. Something to do with the war.

This is the strange story of a state-sanctioned character assassination, and of how, in a violently polarised world, affability, and a good-natured ability to make the best of things and get along with almost anyone, suddenly came to look very much like collaboration with the enemy.

In the summer of 1941, the war was in the balance. The Blitz and the Battle of Britain were over and, alongside its strange new bedfellow Russia, Britain was gearing up for a long struggle with Germany. What mattered most of all now was whether the United States would weigh in by their side.

Polls at the start of hostilities had showed that 95% and more of Americans wanted to stay out of the war. By now Franklin Roosevelt had edged political opinion to the point where he had been able to pass the Lend-Lease Act, at least opening a channel for military supplies and meaningful economic support. But the isolationist lobby were still a formidable force, and the nation was deeply divided.

As much as high politics, public opinion would decide the matter, and much of that would turn on the softest of questions. What was this war really about? Who, at their core, were the British? Why should America fight by their side? Who better to sway the American people than the voices they already knew: writers, entertainers and broadcasters – their every move curated behind the scenes by two formidable propaganda machines.

Britain naturally played on its transatlantic bonds - a shared heritage and common values. A progressive nation, she was united across society in an all-consuming war to defend the proud traditions she stood for. No one embodied this better than the British Ministry of Information’s favourite public figurehead, the playwright and writer J. B. Priestley – best remembered now for that mainstay of the GCSE English syllabus, An Inspector Calls. Priestley was the BBC’s star broadcaster routinely drawing the biggest audiences of the week – not just on the Home Service, but of course on its North American shortwave station. It had been Priestley’s on-air alchemy that had somehow transformed the rout of Dunkirk into that golden miracle of unity and hope, the deliverance of the stranded troops by the great democratic fleet of ‘little ships’. Described by Time Magazine as ‘compact as a beer mug, with a voice as mellow as ancient ale’, his flat Yorkshire intonation and ability to capture a vision of a people fighting as one for a better future was exactly what was needed.

Germany countered with a very different vision: Britain was a deeply hierarchical class-based society, whose manipulative and decadent elite would do anything to keep their grip on the ill-gotten fruits of Empire. This was fertile territory; Ronald Tree, the junior British minister based in Washington, reported that most Americans saw the British as ‘a country of picturesque and servile peasantry ruled over by a land-owning class with affected and effeminate voices’. Noel Coward, much loved by America audiences for his charm and wit, and a regular guest at the Roosevelt’s Whitehouse, was quietly ushered home for fear that his effete public persona was feeding the German narrative.

So where were our quartet of authors while all of this was going on?

C.S Forester was at the heart of things, working discreetly for the British propaganda operation in Washington, placing pro-British content with his many friends in the US media world. Wheatley, who turned out to be Churchill’s favourite thriller writer, had been hired, largely on that basis, for a strange role in a secretive government department in London dreaming up wild outside-the-box ideas for military operations and planning scenarios. A little older, Chandler, a veteran of World War One still battling with PTSD and alcoholism, was out on the West Coast painstakingly reworking the follow up to Farewell my Lovely. Wodehouse, meanwhile, was sitting in a German internment camp.

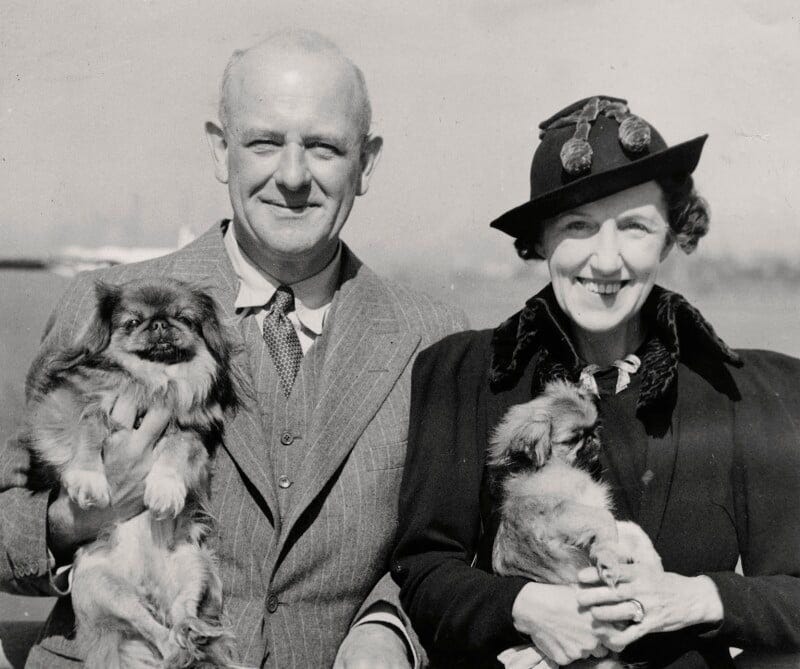

When war broke out, the Wodehouses had been living in comfortable tax exile in the smart resort of Le Touquet on the Northern coast of France – Wodehouse tapping away on his latest book in workaholic bliss, while his flamboyant wife Ethel held court to the local expat community. Taken by surprise by the rapid advance of the German army they had found themselves trapped. Soon Wodehouse, along with every other British man in the area under the age of sixty, had been swept up by the occupying authorities as an enemy alien.

Viewed by his international public as the quintessential Englishman, Wodehouse was in fact in many ways by now more American than British. He first made it big in New York, writing the lyrics for a string of Broadway musicals. Then he moved on to novels and short stories that were essentially the same thing in written form, produced above all for the American market. Once news of his imprisonment reached his well-connected friends in the American entertainment world, they began to lobby for his release. Now realising who they had been holding, German propagandists scented opportunity.

However affectionate, Wodehouse’s outdated cartoon depiction of an idle and frivolous British upper class - one that he had been profitably peddling to his American readers for twenty years and more - fitted all too well with Germany’s favoured stereotypes. He offered the perfect audience too; every weekend, the Saturday Evening Post, seen by media insiders as ‘the nearest thing to a bible for the isolationists’, took his short stories and serialisations into three million opinion-leading middle-class American homes. And how seriously should Britain’s claims of a titanic struggle for the future of civilisation be taken if P.G. Wodehouse, of all people, was cheerfully broadcasting from Berlin.

Wodehouse was in the middle of a time-killing game of camp cricket when a German official arrived unexpectedly and told him to pack his bag. He told Wodehouse he was to be freed, and took him directly to the altogether different surroundings of Berlin’s exclusive Adlon Hotel. Who should he run into on arrival but a German friend from his Hollywood days, who invited him to come into the bar and join a convivial circle of what would turn out to be German intelligence officers. While his old friend went to find him something better to wear, the discussion over drinks turned to sympathetic and helpful suggestions of how he could quickly reconnect with his long-neglected American readership. Why not a radio broadcast?

But first came a long round of interviews with foreign correspondents, mostly American. Emerging into a now radically changed world, the ever-affable Wodehouse got the tone hopelessly wrong. For the New York Times:

I never have been able to work up a belligerent feeling. Just as I am about to feel belligerent about some country, I meet some nice fellow from it and lose all sense of belligerency.

Then an ill-fated radio interview with CBS’s Berlin correspondent broadcast live on their US network. A cheery Wodehouse pondered complacently how the war would affect Britain, ‘whether England wins or not’.

In America the release was picked up the press as a mildly positive good news story. In Britain though, reactions ranged from the ‘disappointed’ to the venomous. The Daily Mirror carried a damning column by ‘Cassandra’, the nom-de-guerre of its star columnist Bill Connor, behind a front-page splash, very much in the same vein, headlined ‘The Price Is?’.

Wodehouse, isolated and oblivious to the British reaction, pondered what he might use as material for his coming broadcast, and decided to brush the dust off the script for a series of jokey talks he had given to his fellow inmates: How to be an Internee. It was innocuous enough material, if laden with an irony and understatement far better suited to his insider audience of fellow prisoners than to a wartime public broadcast. The Germans cared little about the detail. As long as Wodehouse was telling cheerful stories and cracking jokes on German radio, the rest really did not matter. The talk done, he headed off for some rest as a guest of his friend’s fiancée in the Bavarian countryside.

Now, back in Britain, the politicians started to pile in. Questions, ever less coded, were asked in Parliament at four consecutive sittings. Could the Attorney-General give assurances ‘that British subjects who broadcast under enemy auspices will be prosecuted under the Treachery Act’? Was the Ministry of Information watching the broadcasts of any British prisoners liberated in Germany? Were broadcasts being taped to support prosecution? Then finally he was named: the Government, announced the Foreign Secretary Antony Eden ‘had seen with regret that Mr Wodehouse had lent his services to the German propaganda machine’.

The British Minister of Information of the day was Duff Cooper, a senior ally of Churchill visibly struggling with the brief. Determined to lead from the front, he had been widely mocked for reciting Macaulay’s poem on the English defeat of the Armada on national radio in a hopelessly out of touch personal attempt to bolster public morale. The Wodehouse affair was coming to a head at the end of a particularly difficult political week that had seen him losing out publicly in a power battle with other ministries about the control of messaging about the war effort. To cap it all he had been taunted in Parliament for his powerlessness even over the wartime BBC.

As it happened a lunch at the Savoy had been arranged for the following day with a group of half a dozen leading journalists. As they refreshed themselves with pro-Russian toasts in yellow vodka, they asked why he had not resigned; only because it would have been unpatriotic to do so, he said. Inevitably, the conversation turned to Wodehouse: why were the Press not doing more? Connor, one of the guests, countered with an offer to make a no-holds-barred broadcast about the affair on the BBC; but of course, he added, the minister would not dare allow it.

The taunt was a recognition of his reputation. ‘Cassandra’, his column an unrivalled bully-pulpit to the Daily Mirror’s booming working-class circulation, was the journalistic enfant terrible of the day. Still a young man, he had learned his trade in the advertising world before taking journalism by storm, ’armed’, as his own editor put it ‘with intolerance, bigotry and irascibility’. But after just a few more toasts, Connor had been commissioned to speak.

When BBC officials contacted him to organise their editorial sign off, Connor wrote at once to the minister. Unless he had complete control of the text he was going to withdraw. Cooper replied by return: -

If you send me the script personally, I will hand it on to the B.B.C. and will undertake not to interfere with the strength or violence of anything you care to say. Once I have passed it the B.B.C. cannot interfere.

A few days later, on a Friday evening, Cooper’s liaison officer, handed Connor’s scripts to George Barnes, the Director of Talks. It was to be broadcast at the very earliest opportunity, he told the appalled official; this was a direct instruction from the minister. First thing the next morning Barnes met with the his Director General, and the BBC’s Board of Governors was quickly convened. They asked for a meeting with Cooper. The legal advice, they told him, was that they had no choice but to comply, but he needed to know that they were unanimous in opposing the broadcast; if it was to proceed they would need a written ministerial direction.

Connor’s talk went out at quarter past nine on the Tuesday. A little after twenty past he brought things to a close, speaking now as if to Wodehouse himself.

Mr. Wodehouse, you said the other day that you were “quite unable to work up ay kind of belligerent feeling about this war.”

Do you know Dulwich, Mr. Wodehouse? Of course you do. It is the suburb of London where you went to school.

I was there one night not very long ago, Mr. Wodehouse, and something happened that might interest you, who feel so calm and so imperturbable about this war.

It was a peaceful night. Soft and gentle until this quiet was splintered and torn into a thousand screaming shreds as a thousand pounds of explosive travelling at seven hundred miles an hour hit the ground with appalling violence.

Near me under five, ten, fifteen tons of rubble lay human beings. Most of them dead. Some of them alive. A few of them dying.

YOUR countrymen Mr. Wodehouse.

It was quiet. The contrast was rather shocking. One expected noise and excitement. Instead of that there was a silence that was too reminiscent of the grave.

The rescue squads began to work. Someone called for silence. No one spoke.

We listened and with growing horror I knew that we were waiting to hear cries of agony and pain from underneath those crushing loads of battered masonry and brickwork…………

Something savage and unspeakable cruel. You should have been there Mr. Wodehouse with your impartiality, your reasonableness….

…. and perhaps even one of your famous little jokes.

Good night.

And good night to You Mr. Pelham….Grenville……Wodehouse.

The American broadcast aired later that evening. Considerably longer, it included bonus material for a US audience. More an American than a Brit, Wodehouse was Goebbels’ puppet, carefully groomed to manipulate his stateside public. He had been dodging US taxes to boot. It was, said Time Magazine ‘strange stuff for the staid old BBC’.

In truth, by the time Cassandra’s talk went out, the German ploy had already flopped. Clumsy management of the affair in Berlin had landed badly with an American public deeply suspicious of propaganda; the story had quickly morphed from an account of a well-liked icon of Englishness finding a way to rub along with Germany, to one of his disowning by his mother country, and an outraged British reaction to his involvement with German propaganda and manipulation.

It took a time to get the message through to the isolated Wodehouse, about the catastrophic situation he had blundered into, and a few more talks dribbled out. But the show was basically over, and the circus had moved on.

And then Japan attacked Pearl Harbour, and everything that had happened up to that point became suddenly irrelevant.

After ‘Cassandra’s broadcast, the Establishment back in Britain exploded in anger. In the House an MP called for removal of the BBC official responsible for the ‘filthy Postscript’. The Times’s correspondence pages were alight with their readers’ outrage and disgust. Cooper himself bowed to BBC pressure and wrote to the paper:

In justice to the Governors of the B.B.C. I must make it plain that mine was the sole responsibility for the broadcast which last week distressed so many of your readers. The Governors indeed shared unanimously the view expressed in your columns that the broadcast in question was in execrable taste. ‘De gustibus non est disputandem’ Occasions, however, may arise in time of war when plain speaking is more desirable than good taste.

Setting aside the chattering classes, the BBC’s own survey showed that as many as 90% of the public basically agreed. ‘The use of Wodehouse by the Germans was…the most insidious form of propaganda – ostensibly innocent and harmless’. Wartime did not call for half measures, and this national pillorying would act as a clear warning to other British citizens.

Connor himself was unrepentant:

I have never been so pleased over anything in my life…. The BBC is anathema to me… There are Americans who still think English people are Bertie Woosters calling each other ‘Milord’ and I thought the Wodehouse broadcasts would be very helpful [to the isolationist cause].

Connor’s broadcast was Cooper’s parting shot at the MOI. A move abroad had already been set in motion, and just five days later he was replaced by Brendan Bracken, a pressman and media insider altogether better suited for the role.

A few years later, with Paris newly liberated, Cooper was rewarded for his service and political loyalty with his dream job – British ambassador to Paris. Newly established in the smart Bristol Hotel, he and his wife walked into the lift one evening to find that they were sharing a silent and awkward ascent with who else but the Wodehouses. They had been staying at the hotel since the summer. Allowed by the Germans to live comfortably off Wodehouse’s international writing royalties, they had split their time between the Adlon in Berlin and summer visits to aristocratic estates in the German countryside, before moving to Paris in 1943 to escape the worst of the allied bombing.

By now the Wodehouse’s names were on the official list of ‘British subjects living in enemy occupation whose cases required investigation’. Fellow writer Malcom Muggeridge, then a British intelligence officer newly arrived in Paris, was despatched to contact them quietly and assess the situation. But no sooner had he made contact than the French arrested the couple. Muggeridge, on the pretext of concerns for Wodehouse’s health, got him transferred from a police cell to the more comfortable surroundings of a disused maternity unit, then stepped back while the French and British worked out between them what to do with him next.

A military lawyer was flown across the Channel to investigate the case; this was a can of worms best opened abroad. The situation was messy, he reported, the Wodehouses had certainly been ‘unwise’, but in terms of anything that might amount to actual treason, he had found no smoking gun. The papers reached Churchill’s desk. The Wodehouse’s well-liked daughter Leonora had married into the influential Cazalet family, recently beset with the double tragedy of both her sudden death and the wartime loss of her brilliant brother-in-law – as it happened, the godfather to Churchill’s youngest daughter. The Prime Minister scribbled on the papers that he had discussed matters with the family, and that all things considered it would be best for the Wodehouses to be moved quietly back to America. And so it came to pass.

Muggeridge’s encounter with Wodehouse in Paris became the beginning of a lifelong friendship - and later, when Muggeridge became the editor of Punch, an important publishing relationship too. Wodehouse, he wrote ‘is ill-fitted to live in an age of ideological conflict. He just does not react to human beings in that sort of way, and never seems to hate anyone.’

Some years after the war, as if to prove the point, Wodehouse invited Connor to a Manhattan lunch and bluffly buried the hatchet. The whole thing was clearly a misunderstanding. But there was one thing that he had found almost unbearable: hearing his hated middle name on national radio. He could only hope that Connor’s initial stood for Walpurgis or something of the sort! Connor chortled dutifully, and Wodehouse pronounced him now a friend. Between them after that, he was always Walp.

In 1961, to celebrate his eightieth birthday, Evelyn Waugh broadcast a ‘national salute’ to Wodehouse on the BBC. Turning to the Cassandra broadcast, he said that it was:

with great pleasure that I take this opportunity to express the disgust the BBC has always felt for [this] injustice, for which they were guiltless, and their complete repudiation of the charges so ignobly made through their medium.

But Wodehouse’s family were never able to get even a private assurance from British ministers that the famous old writer could visit the United Kingdom without fear of arrest. And so, for the rest of his long life, he never again set foot in the country of his birth.

Finally, at ninety-three, news came that he was to be knighted. At last, he told his friends, the whole matter could be considered closed.

He died just a few weeks later.

Further Reading

For a wider view of Britain’s cultural propaganda efforts in this period, I would strongly recommend Beware the British Serpent, by Robert Calder (2004)

Wodehouse: A Life, Robert McCrum’s excellent 2004 biography has a good account of Wodehouse’s wartime mishaps.

Wodehouse at War, by Iain Sproat (1981), goes into the whole affair in as much forensic detail as you could possibly want.

J.B.Priestley’s BBC Postscript talk on the Little Ships of Dunkirk is recreated as the first segment of this audio book which is well worth a listen.

Few of his critics actually heard Wodehouse’s broadcasts. Long after the war, Wodehouse arranged the publication of what he claimed was the full text, as part of efforts to restore his reputation. I have written a short follow on piece on that here

Great read, really enjoyed it … serendipity put it in my path

My favourite one yet! So interesting